Elizabeth Streb reflects on her career in and out of the dance world

Interview: Siobhan Burke

Interview: Siobhan Burke

As I settled into one of the few remaining seats, digging into the popcorn that came with my ticket, an MC urged us to make some noise and take out our phones—not to turn them off, as most theaters require, but to snap photos and share them widely.

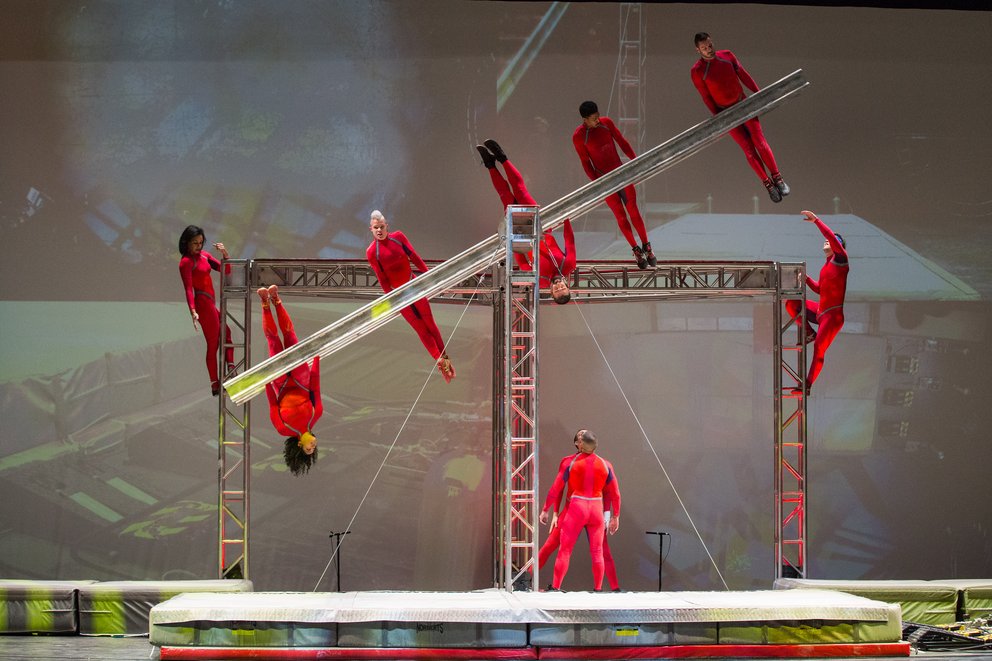

In the fast-paced hour that followed, eight dancers—or action heroes, as they’re officially called—flirted with danger as they flew through the air, squeezed into tight spaces, and smashed into hard surfaces. In one piece, they scaled a towering wheel, running atop it and leaping from its frame; in another, they catapulted themselves from a giant trampoline onto the floor below. Music played, but just as rhythmic was the “thud” of flattened bodies hitting the ground. Mattresses cushioned the blow.

A self-identified “action architect,” Streb founded her company, STREB Extreme Action, in 1985. In 2003, having occupied loft and garage spaces in SoHo and Brooklyn, she settled at what is now SLAM—STREB Lab for Action Mechanics—in a former mustard factory near the Williamsburg waterfront. As the neighborhood has rapidly gentrified, she has retained a kind of democratic outpost. Shows at SLAM aren’t free, but rehearsals are; anyone can walk in and see the company at work or stop by to use the water fountains and bathrooms. “I wanted to reinvite the idea of interruption and strangers gazing back into my manifold, the way it is when an artist is younger,” she says. “The interruption is constant when you’re nobody.”

By the time Streb founded SLAM, she was not nobody, having won a Guggenheim Fellowship, a McArthur Genius Award, and two Bessies (New York Dance & Performance Awards). It was almost by accident that she wound up in the dance field. Adopted by working-class Catholic parents at age two, she grew up in Rochester, New York, playing sports and learning to draw. In college at SUNY Brockport, she majored in dance on a whim, with no formal training. While she has won acclaim as a choreographer, she sees her work not as “dance” but as “action.”

I sat down with Streb in May to talk about her conflicted relationship to the dance world, her resistance to performing for the elite, and how her company has become more inclusive over the years.

Siobhan Burke: How has your work changed since you moved to SLAM?

Elizabeth Streb: I was 52 years old when I signed the lease at SLAM in 2002. In the dance world I got what I needed to keep going, this award or that review. I thought, am I supposed to keep working on my career for the rest of my live long days? I clearly felt I had done my career. I also noticed that the art world, the dance world, is very elitist, very white, and I wanted to represent the whole world. It wasn’t really a gesture toward fairness, it was just what I felt. I had an all-white company then. My partner kept saying, “Can’t you do your auditions in Harlem?” I had this attitude that STREB was for guilty white Catholics—that was my excuse. We always had open auditions, but people of color started to come in the door, and I hired them. That’s how things started to evolve, so that when we’re onstage, it’s the whole world, and anyone glancing up can relate to it—even though audiences for dance are mostly white.

SB: When was this?

ES: It took a couple of years after we opened SLAM in 2003, so maybe in 2005 or 2006, the company started to become diversified.

SB: What inspired the shift toward a more racially diverse company?

ES: My girlfriend. She’s British, but she worked for MADRE [the international women’s human rights organization] and was a journalist who dealt with the Irish crisis. When she was in her teens, she’d go to Northern Ireland and see what was going on there. That’s not a race thing, but it’s definitely a class thing. She just had a broader worldview than I did coming from upstate New York. She would say, “What are you doing?”

If you’re working class and white and from upstate New York with high-school-educated parents, you grow up in a racist household. My adoptive parents, they didn’t have the beautiful impulse that educated people have to question everything, or at least a little four-year practice in college of questioning everything.

I didn’t notice all that when I was first working. But I feel that the content isn’t the moves you’re making, it’s who makes those moves, how they get performed, what history every body is bringing to the room. It’s a whole mixture that weaves into the product that ends up having its own effect out of your control.

SB: You also mentioned reaching a certain level in your career and wanting to be more populist.

ES: That’s my dream, but we’re trapped inside the vestibule of the art world. I’m stained with the film of art. Everyone can see it and smell it. And there is no distribution system in the dance world. I’m performing for the elite. That’s the tragedy. I’m 68. Am I really going to be performing for the elite for the rest of my life? Maybe there are forms in the dance world that can get distributed across the rugged arena of America, but there doesn’t seem to be a tributary that addresses that.

I have a garage, though, and it’s funky. And our audience—no dance people come to our shows. SLAM is essentially an experiment to do the thing I want to do, to perform for the every-person within my zone.

SB: Aside from opening rehearsals to the public, have you done anything to try to reach a wider audience?

ES: I think the only thing that can do that is really the nature of the work. I have an assessment about how close you let danger come to you. It’s a very quotidian analysis, but you notice that wealthier, more privileged people have bigger yards, higher fences. In 1995 to ’97 we, were in a garage in Bed-Stuy [Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn] before the neighborhood was more gentrified. I would see people at the bodega, and their faces—I saw so many people with face scars, women and men. The scarification of a body gets lessened the larger margin of protection you have. This is my analysis. If you can keep harm away from you, you get to protect yourself and become more sealed in, but that’s only through privilege.

The nature of my work is that if you want to learn to fly, you’re going to get a little hurt, so stop acting like if you get hurt it’s wrong. We try not to get hurt, obviously; the idea is to get a little hurt, not too hurt. In every physical artistic form, including the circus, they don’t really land. They spend all this technical time camouflaging gravity, pretending there is no force pulling you down. I decided to land, like really with the full force of gravity, and I think that began to register with working class people, because they can’t keep harm away from them. I deeply believe that dance has murdered itself by ignoring the one force we have access to: gravity. And I think that we, STREB, represent that, not just artificially or aesthetically but rough and hard. It brings in a different audience. They look at that and they totally understand.

SB: That’s interesting—these ideas of protection and distance.

ES: I really find dance pretty boring.

SB: All dance? Is there any dance you like?

ES: I was an accidental interloper. All through grammar school I took visual arts classes. My talent was drawing; I had that hand-eye coordination. I was also on the varsity team for basketball and baseball. I did downhill skiing and had a motorcycle. I thought I would be a P.E. teacher. But then there was this art thing. When I had to choose a major at SUNY Brockport, I saw dance and thought, I’ll major in dance. I can move and draw, and that’s the art of movement.

They took me into the program because it was so new, but I really couldn’t dance. They wanted you to count to the music, look in the mirror. With the velocity and impact of motorcycle riding and basketball and baseball, I was just like, why? How can you move and see yourself? How can you possibly count without affecting the way you’re moving? And doing all this technical work just to erase the effect of that?

I love Trisha Brown, of course, and Merce Cunningham. I like the intellectual choreographers. Dancing around is just not my thing. I find it aesthetically uninteresting and purely privileged. I think people want to dance; I really don’t believe they want to watch people dancing. If you say you like to go and watch dance, I don’t believe you. And if it’s true, then why is it just us in the audience?

SB: Watching your work, I find myself thinking, “I could never do that! How do they do that?” Is that an important part of it for you?

ES: No, I think the opposite. I think people look at a ballet dancer and they know that somewhere in their bodies it would take 20 years to do that. But a lot of people think, “Hey, I could do STREB.” In our classes at SLAM, we have 800 students a week, kids and adults. They’re not all on the big machines obviously, but they fly and learn how to land on different bases of support, rather than just right side up.

My search is for the iambic pentameter of action. I say this a lot, but I think it’s still a salient question: Why does movement make people cry? What part of movement, just because of its abstract essence, would cause people to feel choked up inside? That’s the goal of a dramatic theatrical language. I think dance has skipped so many parts of that, is so satisfied with itself, a whole lot of people making believe that the only base of support is the bottoms of my feet and I’m going to dance to music, or not dance to music, but just go so slow. What about speed, acceleration, momentum? You’re accepting the fact that you can’t slam into the wall. You’re slowing down because you know the edge of the stage is coming and you turn around. It’s always medium speed, medium effort of force, maybe a little more because you want to do a tour jeté, but — I think it’s an unexamined form to the nth degree.

SB: What about people working now like —

ES: I like Abby Zbikowski. I went to Bill T. Jones’s gala a week ago or so, and one of the people who works at SLAM, Fiona, she was doing this dance by Abby Z. I really was impressed. Abby Z was there and I hadn’t met her, and I was just like, wow, that’s extraordinary, thank you. And I bet she’s a working-class girl. Why do working-class girls take it to another level? I was extremely thrilled to see that. I also saw a show by Alice Sheppard, who’s a disabled dancer. Thank you! That is the most gorgeous thing. I was just like damn! It was beautiful and powerful and really physical.

SB: What about descendants of Trisha Brown, people working in that lineage?

ES: I think that people add to the vocabulary of the field with every move they make. In my analysis of the movement, I don’t even think I’m dance anymore. There will be a place in the American cultural geography that will be action, and it won’t be circus or dance or sports. It’ll be what we’re doing, with the invention of machines like music invents its instruments.

SB: It seems like you’ve distanced yourself from dance but really respect certain choreographers — you also mentioned Lucinda Childs and Balanchine. You don’t dismiss their work, it’s just not what you’re interested in.

ES: Right. I’m at home in the dance world. I really can’t believe I found a place there. I didn’t think that was going to happen.

At “Kid Action” you will transform your energy into spectacular movements and explore physical boundaries with the Elizabeth Streb’s ‘Action Heroes’: in a combination of physical training, dance, stunts and acrobatics you confront gravity, speed and impact.

12.8., 14:00–15:00 | HAU3 Houseclub

Age 8–12

Workshop Language German & English

Apply under begleitprogramm@tanzimaugust.de

Participation free of charge

max. 20 participants