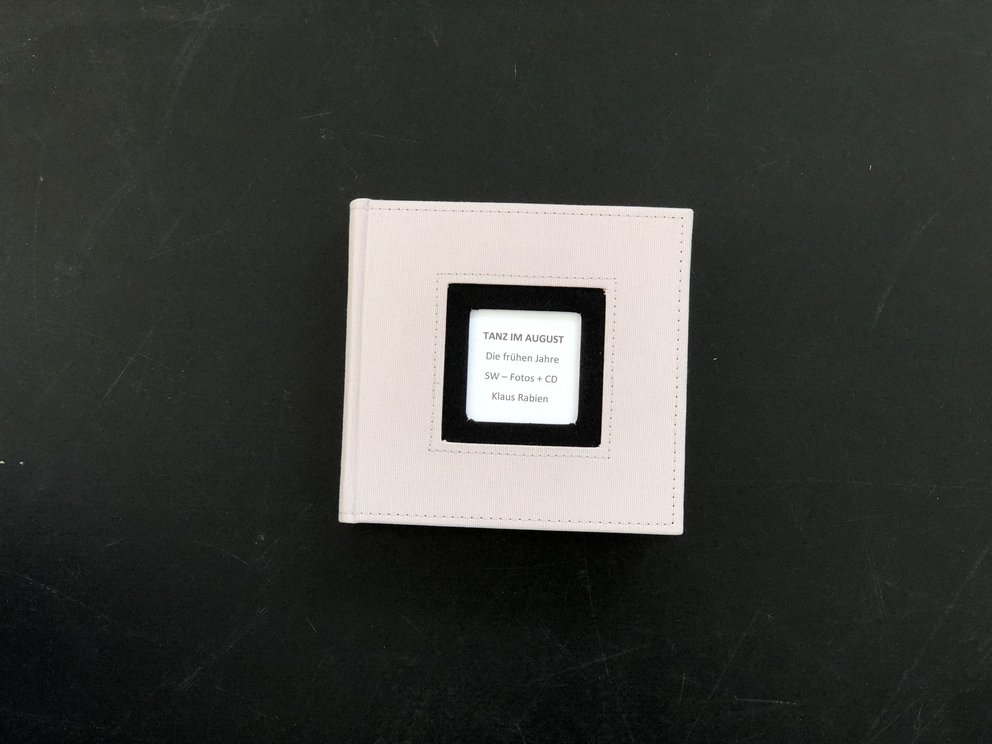

If the research for “FÜR IMMER TANZ – 30 Jahre Tanz im August" didn’t throw up these kinds of unexpected surprises, the task of searching and collecting could get boring. Klaus Rabien was one such surprise. To begin with, I was told about a photographer who was actually a baker – a master of the 'Baumkuchen', in fact.

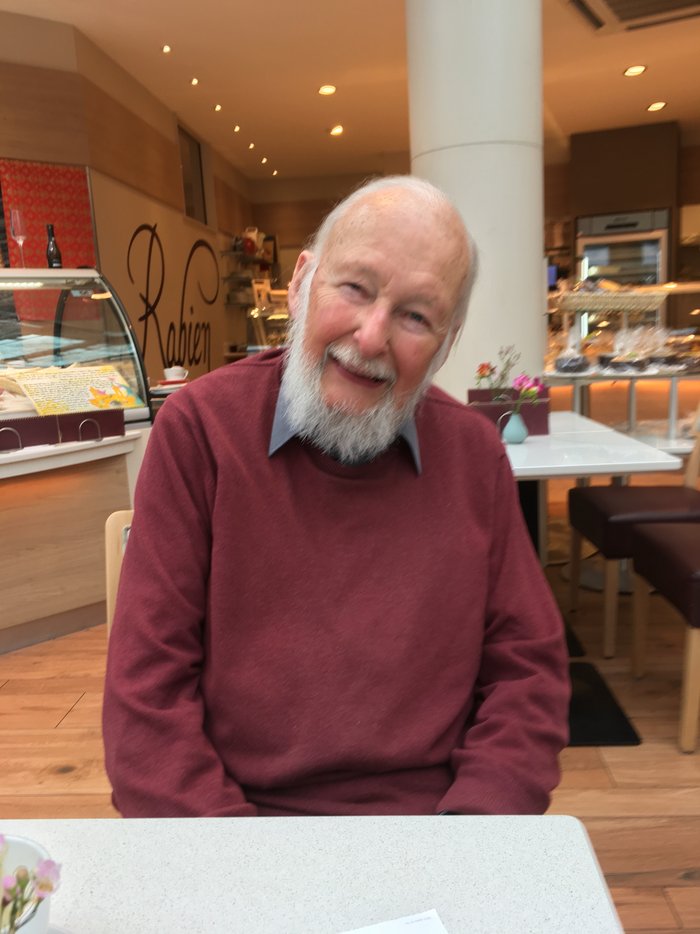

Using his name, I found the Konditorei Rabien in Steglitz, but still couldn’t uncover the photographer. I visited the pâtisserie to have some cake and learnt from the service staff that yes, the big boss was a photographer, but wasn’t in at the moment. “Leave your telephone number and he’ll get back to you,” they said. And that’s exactly what Klaus Rabien did. We met in the shop, a family-run business that has been handed down through generations; a real pâtisserie in which neither calorie tables nor vegan ingredient hit-lists are present to spoil your appetite for CAKE. Only the indication of whether a cake is “alcohol-free” or not assists customers with their decision. A range of almost-forgotten delicacies huddle together in the display cases, while parcels of ‘Baumkuchen' and pralines also compete for the customer’s attention – a paradise for anyone who doesn’t view sugar as their primary nutritional enemy. Klaus Rabien is a genuine Berliner – bright, quick-witted, and with a pinch of humour sprinkled in too.